(Photo: Iowa Soybean Association / Joclyn Bushman)

An unwelcomed three-peat

October 23, 2024

In any sport, a three-peat is a good thing.

In the NBA, the Boston Celtics, Chicago Bulls and the Los Angeles Lakers have all claimed at least three championship titles in a row.

In the NFL, the Green Bay Packers won three titles in a row from 1965-67; the Kansas City Chiefs are hoping in 2025 they can claim their third Super Bowl trophy following victories in 2023 and 2024.

And in international swimming, Americans Michael Phelps and Katie Ledecky have struck gold each at four consecutive Olympic games, given them a four-peat.

But when it comes to transporting soybeans down the Mississippi River, a three-peat is not welcome news.

Low levels limit barge transportation

“Unfortunately, we are experiencing an unwelcome three-peat with low water levels on the Mississippi River during harvest season, when we need our supply chain to be operating at full throttle,” says Mike Steenhoek, executive director of the Soy Transportation Coalition. “We experienced low water in both 2022 and 2023 and now, once again, in 2024.”

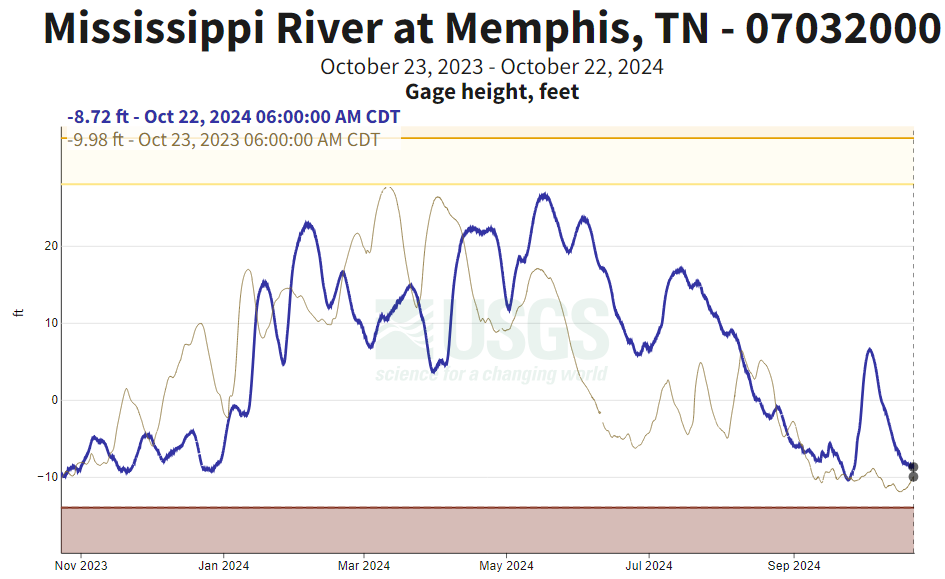

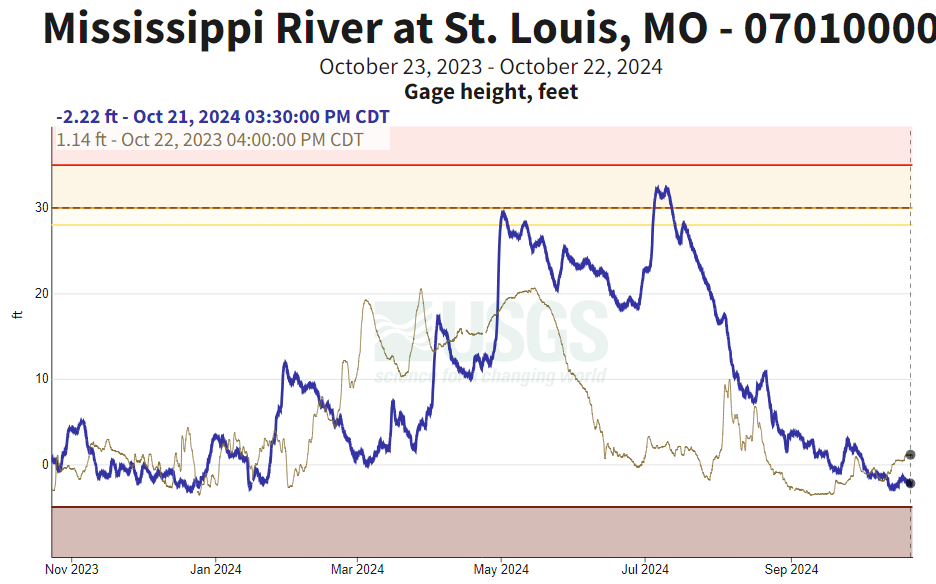

The U.S. Geological Survey this week highlighted low water levels at both St. Louis, Mo., and Memphis, Tenn., similar to where the river was at a year ago (see charts below).

Steenhoek says the news is frustrating, especially given a moisture-filled spring and summer.

“Water levels were quite robust during the spring and early summer,” he says. “However, once we progressed past mid-July, precipitation declined significantly, which caused a steady and dramatic decrease in water levels. One can see the short-lived 15+ foot spike in water levels at Memphis due to Hurricane Helene. Once that surge of water passed through the system, water levels at Memphis quickly returned to where they were earlier.”

Steenhoek says lower levels on the Mississippi means fewer beans can be shipped to global markets around the world.

“For each foot of draft reduction on the river, an individual barge is loaded with 7,000 fewer bushels (200 tons) of soybeans,” he says. “In certain areas of the river, we are seeing several feet of draft restrictions due to low water. In addition, the lack of water will narrow the shipping channel, which limits the number of barges that can be attached together to form one single flotilla or tow.”

Steenhoek says depending on the location in the river, tow sizes are being reduced from 10-15% at minimum and upwards of 30-40%.

He added that what makes barge transportation so economical is the ability to load individual barges with significant volumes of freight while attaching many barges together to form a flotilla or tow. Low water conditions on the river, Steenhoek says, “attack both of these features.”

Some good news

Because of the low water levels, barge companies are forced to limit the soybeans, grain and other cargo they carry in order to prevent barges from potentially getting stuck. In the end, that hurts the bottom line for farmers.

About 60% of U.S. grain exports are transported by barge to New Orleans via the Mississippi River. Barge transportation, of course, is a more efficient way to ship soybeans, corn and wheat. According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), a typical group of 15 barges lashes together carries as much cargo as about 1,000 trucks.

The USDA’s Grain Transportation Report showed that for the week ending Oct. 12, barged grain movements totaled 568,454 tons. The good news was that this was 54% more than the previous week and 15% more than the same period last year.

For the week ending Oct. 12, the report indicated that 356 grain barges moved down river - 110 more than last week. There were 851 grain barges unloaded in the New Orleans region, 12% more than last week.

Weather woes

Iowa State Climatologist Justin Glisan says it’s not clear if the current dry weather or any future precipitation in the Upper Midwest will continue.

“The short-term outlooks through the end of October and into November show higher probabilities of warmer than average temperatures and a slightly elevated wet signal,” he says. “We are also in a “La Nina Watch” with a 60% chance a transition to this phase in the October-November timeframe.”

While typical La Nina winters are colder across the Dakotas through Montana and the Pacific Northwest, and southern states are generally warmer and drier, “we don’t have clear guidance for Iowa,” Glisan says.

In 2020-22, there were three consecutive La Nina winters, which is only the third time this has happened since 1950. With 152 years of records, they ranked as such for temperature/precipitation:

- 2020: 23rd warmest/ 62nd driest

- 2021: 63rd coldest/52nd driest

- 2022: 69th warmest/16th driest

Another supply chain challenge

Steenhoek says Mississippi River levels are just another gut punch to farmers, who already face concerns with lower market prices and high input costs.

“At a time in which soybean exports are confronted with numerous challenges, it is our hope that our supply chain can encourage profitability, rather than be one further impediment,” he says. “Unfortunately, we continue to experience numerous supply chain challenges. Low water on the Mississippi River is one compelling example of this.”

Back